Cassiopeia, the elegant constellation which hovers year-round in the skies of the Northern Hemisphere is typically recognized by its more simple asterism shaped like a “W” with a slight tilt on one side. (An asterism is a prominent pattern or group of stars, typically having a popular name but smaller than a constellation.)

The constellation represents the queen of Aethiopia*, the mother of Andromeda in Greek mythology. It’s interesting to note that the Andromeda constellation lies adjacent to Cassiopeia in the night sky. Cassiopeia as a constellation has been known for a long time, as it was listed as one of the 48 original constellations in the 2nd century by Greek astronomer, Ptolemy. Today that list has been extended to 88 official constellations by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

(*Aethiopia were ancient lands in the area of the upper Nile, not to be confused with modern day Ethiopia.)

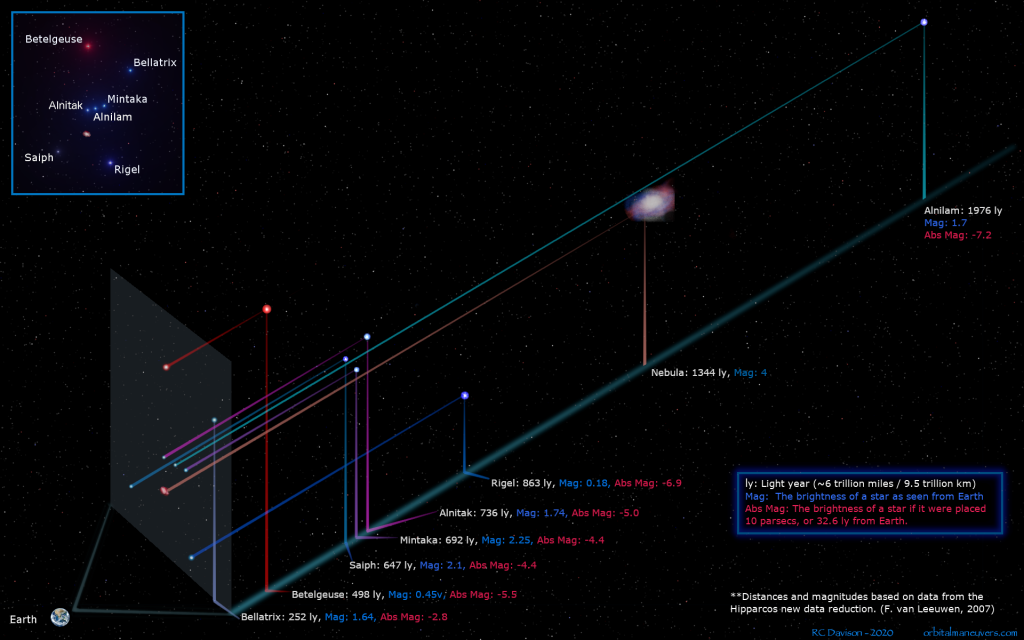

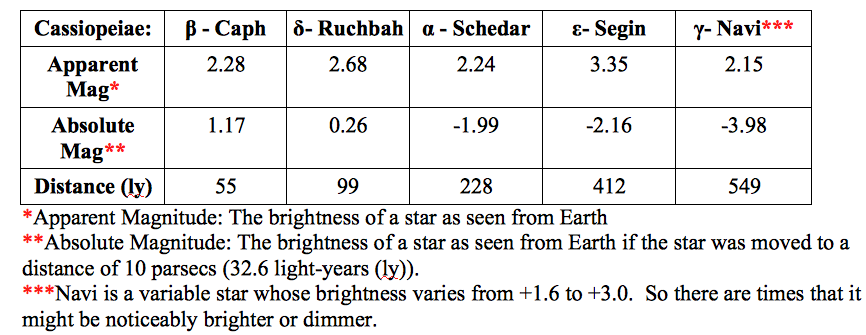

The asterism is made up of five stars that can be seen in the illustration below, which shows their distance from Earth and their apparent and absolute magnitudes.

The table below lists the stars that make up the asterism, arranged in order of their distance from Earth:

What makes Cassiopeia’s asterism remarkable is that four of the five stars appear to be very close in brightness with their apparent magnitudes varying about 1.5 times from the dimmest, Ruchbah (2.68), to the brightest, Navi (2.15). The fifth star, Segin, is notably dimmer than the rest (3.35) but still is fairly bright. (Remember, the more positive the number, the dimmer the star.) This uniformity in brightness gives the impression that the stars are all the same size and distance from Earth.

Being about the same brightness is, in itself, not all that noteworthy until you look at their absolute magnitudes, their distances from Earth and how they work together to create the constellation we see and give us Cassiopeia’s illusion.

To understand what’s happening one has to remember that light has a property that its intensity diminishes by one over the distance squared (1/d2). A candle two feet from you is ¼ the brightness it is one foot away. So one naturally expects to see the stars get dimmer the further away they are. But, that’s not what we see with Cassiopeia.

Starting with the closest star, Caph, 54 light-years from Earth, and moving further out we see that each successive star’s absolute magnitude is more negative (i.e. brighter) than the preceding one:

- Ruchbah is twice as far as Caph, and it’s 3.7 times as bright – almost 4 times. “If” Caph and Ruchbah had the same absolute magnitude, and Ruchbah was at twice the distance of Caph, we would expect its apparent magnitude to be ¼ that of Caph’s, but that’s not what we see. Ruchbah is almost 4 times brighter. Its intrinsic brightness is such that it compensates for being twice as far away. So it appears to us to be about as bright as Caph.

- Likewise, Schedar is 4.2 times further and 18 times brighter. If we take the square of the distance – (4.2 x 4.2 = 17.6) – almost 18. Schedar’s intrinsic brightness compensates for the distance, again making it appear to be as bright as Caph to us.

- Navi is 10 times further but 115 times brighter – that’s pretty close to 10 x 10 = 100 – the square of the distance. Again Navi’s brightness compensates for the greater distance.

- Segin doesn’t follow this pattern and is dimmer than the rest. If it had an absolute magnitude of -3.1 instead of -2.16, it would be about 50 times brighter than Caph and at its distance from Earth it would have about the same apparent magnitude.

So, through random chance of the stars’ distance and intrinsic brightness, the stars of Cassiopeia very closely compensate for the 1/d2 reduction in the intensity of light over distance. So we see them to be all about the same brightness from here on Earth.

(Note that intervening dust and gas along our line of sight can cause the star to appear dimmer and therefore perceived to be further away than it really is. This is one of the many sources of error that astronomers have to take into account when measuring the brightness and distance of stars.)

So how do these stars make up for their distance?

The other stars in the asterism are hotter and bigger than Caph, especially the more distant stars. Caph is a yellow subgiant, about as hot as our Sun but 28 times more luminous. Navi and Segin are very hot blue stars with luminosities of 161 and 57 times Caph’s luminosity, respectively. Schedar, although a cooler orange-red giant star, is 32 times more luminous than Caph. Even Ruchbah, a more typical main sequence star, is 2.3 times more luminous than Caph.

So, how bright a star appears to be in the night sky is determined not only by its distance and the dust and gas that might lay between it and the observer, but it also its intrinsic brightness. This is a property of the star which depends on how big and how hot it is. So Mother Nature’s distribution of stars in the cosmos can conspire to present us with the illusion, at least for Cassiopeia, that all these stars are the same size and distance from us.

Till next time,

RC Davison

References:

Navi information: https://www.universeguide.com/star/4427/cih